When stories speak more truth than dog DNA analysis

Researchers turned to an unlikely source in a doggy DNA study. Here's why their technique should be used more often.

I am as guilty as anyone of hyping up the power of DNA analysis. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing has shown that normal people (not just freaks like me) want to answer questions about their own ancestry, disease risk, and evolution by probing their genes. When I’m being optimistic about this tech, I think of the genetic code like a universal book that all living things are born with. The book itself is some combination of a self-help Living for Dummies and a massive guest book that all your ancestors have signed and dated. DNA analysis promises to let us read that book, which is truly awe-inspiring.

But have you ever read a giant book? They’re clunky, unwieldy, and confusing. If you have specific questions about a trait, behavior, or pattern (as many scientists do) it’s not always easy to find the right page of the DNA book. (I’m almost done torturing this metaphor, I promise.) In cases like these, instead of thumbing through yellowed, half-eaten pages, wouldn’t it be easier to ask someone who just knows the answer?

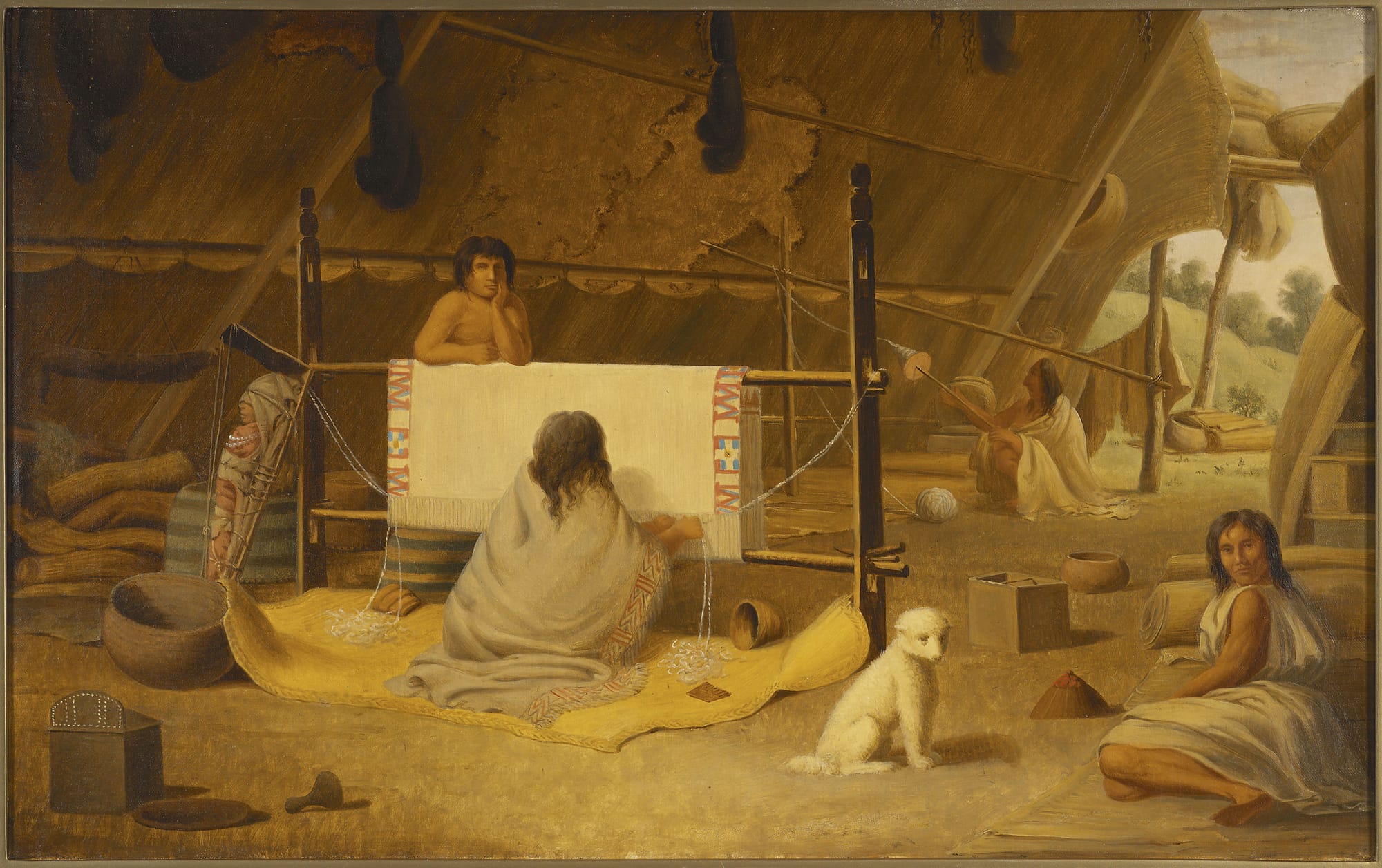

A study in Science combines genomic sequencing with the interviews of Indigenous elders from a handful of Nations and communities to investigate the creation and extinction of a fluffy white dog breed. Salish woolly dogs grew thick coats that Coast Salish people shorn and wove into blankets, and their decline throughout the 19th century and ultimate extinction is still not well-understood. Researchers extracted genetic material from a preserved pelt of an Indigenous dog named Mutton that died in 1859. Based on their analysis, Mutton was most similar genetically to a lineage of pre-colonial dogs, which disappeared after European colonization.

But the information the researchers gathered from interviewing seven Coast Salish elders revealed why Mutton’s ancestry was the way it was. Despite the introduction of European dogs to the region, Musqueam elder Debra qwasen Sparrow told researchers that Coast Salish women carefully maintained woolly dog lineages and prevented them from interbreeding with hunting or village dogs to preserve their unique coats. Selective breeding preserved the dogs’ traits, but it also made them vulnerable to inbreeding and population bottlenecks. A nonagenarian, Stó:lō elder Rena Point Bolton, told the researchers that British colonizers in modern-day British Columbia forced her great-grandmother to give up her woolly dogs; another elder explained that the British outlawed traditional weaving practices, including the ones for making woolly dog blankets.

DNA is an invaluable historical tool, and sometimes it’s the only option when the history in question predates today’s living organisms. But when it’s not the only option, combining genetic analysis with contemporaneous accounts can prove even more powerful. After all, a genetic book is only as valuable as its librarian.